Primaquine & Alternative Eligibility Checker

Determine if primaquine or tafenoquine is appropriate for your malaria treatment

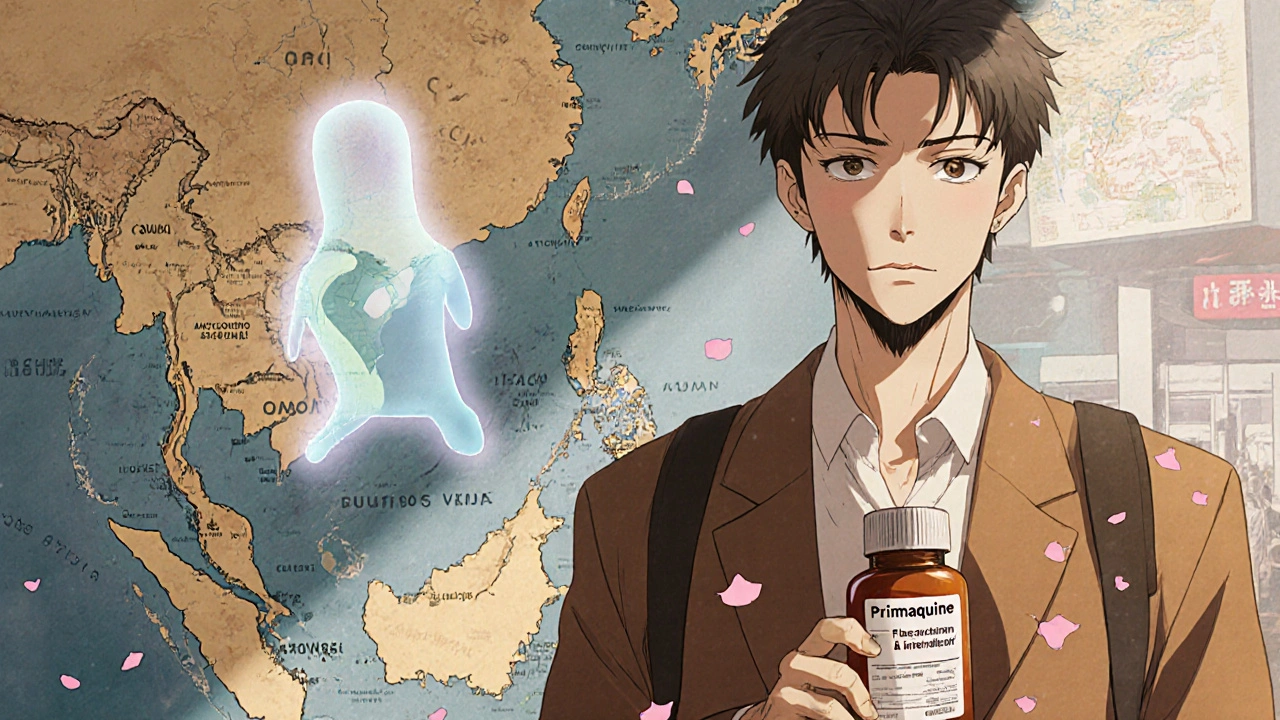

Primaquine is a drug you don’t hear much about unless you’re traveling to a malaria-prone area or treating a specific type of infection. But for people heading to parts of Southeast Asia, South America, or Africa, it’s often the final piece of the puzzle when it comes to stopping malaria from coming back. The problem? It’s not for everyone. Some people can’t take it. Others get sick from it. And that’s where alternatives come in.

What Primaquine Actually Does

Primaquine isn’t used to treat the initial fever and chills of malaria-that’s usually done with artemisinin-based drugs. Instead, it targets the dormant liver stages of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale, two types of malaria parasites that can hide in your liver for weeks or months and then wake up to cause a relapse. Without primaquine, you might feel fine for a month after returning from a trip… then crash again with full-blown malaria.

It’s also used in combination with other drugs to kill the sexual forms of the parasite, stopping transmission. In some cases, it’s the only drug that can do this. But it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution.

Why Primaquine Isn’t an Option for Everyone

Primaquine can cause serious side effects in people with a genetic condition called G6PD deficiency. This affects about 400 million people worldwide, especially those of African, Mediterranean, or Southeast Asian descent. If you have it and take primaquine, your red blood cells can break down dangerously fast-a condition called hemolytic anemia. It can be life-threatening.

Doctors test for G6PD deficiency before prescribing primaquine. But in many places, testing isn’t available. That’s why alternatives matter. Even if you’re not at risk, some people just can’t tolerate the nausea, stomach cramps, or dizziness that come with it.

Chloroquine: The Old Favorite

Chloroquine was the go-to malaria drug for decades. It’s cheap, well-studied, and works well against some strains. But here’s the catch: most malaria parasites in Southeast Asia, South America, and Africa have become resistant to it. In places like Thailand or Cambodia, chloroquine is useless for treating the main blood-stage infection.

It doesn’t touch the liver stages either, so it won’t prevent relapses. That means even if you take chloroquine to treat your symptoms, you’ll still need something like primaquine to stop it from coming back. So while chloroquine might be part of the treatment plan, it’s not a replacement for primaquine’s unique role.

Artemisinin-Based Combination Therapies (ACTs)

ACTs are now the standard for treating uncomplicated malaria. They combine artemisinin (a fast-acting compound from the sweet wormwood plant) with a longer-lasting partner drug like lumefantrine or mefloquine. These work fast, are effective against resistant strains, and have fewer side effects than older drugs.

But here’s the gap: ACTs don’t kill the dormant liver forms. So even if you take an ACT and feel fine, you’re not protected from a relapse. That’s why ACTs are often followed by a course of primaquine in areas where P. vivax is common. In some cases, like in Papua New Guinea or the Amazon, health workers give a single dose of primaquine along with the ACT to cover both stages at once.

Tafenoquine: The New Alternative

Released in 2018, tafenoquine is the first real alternative to primaquine that does the same job-killing dormant liver stages-but with a big advantage: one dose. Primaquine requires 14 days of daily pills. Tafenoquine is taken just once, right after you finish your main treatment.

It’s just as effective as primaquine in preventing relapses. But it also carries the same risk for people with G6PD deficiency. You still need testing before taking it. And it’s much more expensive. In Australia, a single dose can cost over $200. In many low-income countries, it’s not available at all.

For travelers who hate taking pills for two weeks, tafenoquine is a game-changer. For others, especially those with limited access to testing or money, it’s not an option.

Other Options: Atovaquone-Proguanil and Mefloquine

Atovaquone-proguanil (sold as Malarone) is often used for prevention, not treatment. It blocks the parasite in the liver before it can multiply. But it doesn’t clear out existing dormant forms. So if you’ve already been infected, it won’t stop a relapse.

Mefloquine is another preventive drug. It’s taken weekly and can be used in areas with chloroquine resistance. But it has serious neurological side effects-bad dreams, anxiety, even hallucinations in rare cases. It’s not used much anymore, especially in the military or among people with mental health conditions.

Neither of these replaces primaquine’s role in preventing relapses. They’re prevention tools, not cure tools.

When to Choose What

Here’s a simple decision guide based on real-world scenarios:

- If you’re traveling to a high-risk area and haven’t been infected yet: Use atovaquone-proguanil or doxycycline for prevention. Primaquine isn’t used for prevention.

- If you’ve been diagnosed with P. vivax or P. ovale malaria: You need primaquine or tafenoquine to prevent relapse-unless you’re G6PD deficient.

- If you’re G6PD deficient and have P. vivax malaria: You’re stuck with weekly chloroquine for 8-10 weeks to suppress the parasite, even though it’s not ideal. There’s no perfect alternative yet.

- If you’re in a country with no access to G6PD testing: Doctors may avoid primaquine altogether and rely on repeated chloroquine courses, even though this increases the risk of drug resistance.

What’s Missing from the Market

There’s no perfect substitute for primaquine yet. Tafenoquine helps, but only if you can afford it and get tested. Chloroquine doesn’t solve the relapse problem. New drugs are in development, like KAF156 and cipargamin, but they’re still years away from being widely available.

What’s needed is a drug that kills dormant liver stages without harming G6PD-deficient people. That’s the holy grail. Until then, the choice comes down to testing, cost, access, and tolerance.

Real-World Example: A Traveler’s Story

In 2023, a 32-year-old woman from Adelaide returned from a two-week trip to Bali. She had a mild fever and fatigue a week later. Blood tests confirmed P. vivax malaria. She was given artemether-lumefantrine (an ACT) and told she’d need primaquine for 14 days.

She started the primaquine course but got severe nausea and dizziness after day three. She stopped. Two weeks later, she was back in the hospital with a full relapse. Only after a G6PD test came back normal did her doctor realize she’d had a bad reaction to the drug itself-not her genetics. She tried tafenoquine next time. One pill. No side effects. No relapse.

Her story isn’t rare. Many people stop primaquine because of side effects, not because they’re G6PD deficient. That’s why alternatives matter-not just for safety, but for compliance.

Final Thoughts

Primaquine isn’t perfect. But for now, it’s still the most reliable way to stop malaria from coming back after infection with P. vivax or P. ovale. Tafenoquine is a better option if you can get it and afford it. Chloroquine and other drugs can’t replace its unique function.

If you’re planning travel to a malaria zone, talk to a travel clinic before you go. Get tested for G6PD deficiency if possible. Ask about tafenoquine. Don’t assume primaquine is your only choice-because it’s not. But don’t skip it either, unless you have a real alternative lined up. One missed dose can mean months of uncertainty.

Can I take primaquine if I’m pregnant?

No. Primaquine is not safe during pregnancy. It can harm the developing baby, especially in the first trimester. Pregnant women with malaria are usually treated with chloroquine or quinine, followed by close monitoring. After delivery, primaquine can be considered if the mother is G6PD-deficient and needs to prevent relapse.

Is tafenoquine better than primaquine?

Tafenoquine is better in two ways: it’s a single dose instead of 14 days, and it’s more effective at preventing relapse in some studies. But it’s not better for everyone. It’s more expensive, requires G6PD testing like primaquine, and isn’t available everywhere. For people who struggle with daily pills, it’s ideal. For those with limited access or budget, primaquine remains the practical choice.

Can I use chloroquine instead of primaquine to prevent relapse?

No. Chloroquine only kills the active blood-stage parasites. It does nothing to the dormant liver forms that cause relapses. Taking chloroquine long-term can suppress symptoms, but it doesn’t cure the underlying infection. That’s why relapses happen. Primaquine or tafenoquine are the only drugs that target the liver stage.

What are the most common side effects of primaquine?

The most common side effects are nausea, vomiting, stomach cramps, dizziness, and headache. These usually go away after a few days. More serious side effects-like dark urine, yellow skin, or extreme fatigue-can signal hemolytic anemia in people with G6PD deficiency. If you feel worse after starting primaquine, stop and get medical help immediately.

Do I need a prescription for primaquine or tafenoquine?

Yes. Both drugs require a prescription. They’re not available over the counter because of the risk of serious side effects. You must be tested for G6PD deficiency before taking either one. Even if you’ve taken primaquine before, you need to be tested again if it’s been more than a year or if your health has changed.

Primaquine is such a weird drug-like the quiet kid in class who saves the day but nobody remembers their name. I took it after a trip to Cambodia and honestly? The nausea was brutal. But I didn’t relapse. Worth it. Still, I get why people bail on it.

Ugh I hate how doctors treat this like it’s a one-size-fits-all solution. I’m G6PD deficient and they still tried to push primaquine like I’m just being dramatic. Like I’m the problem, not the system. No testing. No options. Just guilt trips.

Chloroquine for 10 weeks? How quaint. Only in the developing world do people still treat malaria like it’s the 1950s. Tafenoquine exists. It’s just that most clinics don’t care enough to stock it. Or afford it. Sad.

Big shoutout to the doc who actually tested me for G6PD before prescribing primaquine 🙌 I was terrified but it saved my life. Also tafenoquine? Game changer. One pill. Done. No more daily pill anxiety. If your clinic doesn’t offer it, ask again. And again. And again.

primaquine is trash. just take chloroquine and call it a day. people overcomplicate everything

Let’s be real - if you’re not getting tested for G6PD before taking primaquine, you’re not being careful, you’re being reckless. 🤦♀️ And yes, I’m talking to you, ‘I’ve taken it before so I’m fine’ people. Genetics don’t change. Your luck might.

It’s fascinating how a drug that’s been around since the 1950s still holds such critical, irreplaceable weight in global health. The fact that we haven’t developed a safer, equally effective alternative speaks volumes about pharmaceutical priorities. Profit over patient. Always.

Wait… so tafenoquine is just primaquine with a better marketing team? And a $200 price tag? I’m not impressed. If it still kills G6PD-deficient people, what’s the point? Just call it Primaquine 2.0 and charge extra.

People act like primaquine is some magic bullet but honestly half the time it just makes you feel like garbage for two weeks. I know someone who threw up every day and still got a relapse. That’s not treatment, that’s torture with a prescription

As someone who’s lived in rural India for 10 years, I’ve seen doctors give chloroquine for 8 weeks straight to people who can’t afford testing. It’s not ideal but it’s survival. We need real solutions, not just fancy pills for rich travelers

Why are we even talking about this? America’s got the best doctors and the best drugs. If you’re getting malaria abroad, you shouldn’t have gone. Primaquine? Tafenoquine? Just stay home and save your money

OMG I JUST GOT BACK FROM VIETNAM AND I DID THE TAFENOQUINE THING AND IT WAS A LIFESAVER 😭 ONE PILL AND I WAS DONE. NO MORE DAILY PILLS. NO MORE NAUSEA. I DIDN’T EVEN THINK ABOUT IT AFTER THAT. Y’ALL NEED TO ASK YOUR DOCTOR ABOUT THIS. IT’S A GAME CHANGER 🙌💊

Wait… so you’re saying… we have a one-dose alternative… but only if you’re rich? And tested? And in a country that can afford it? And the drug is still toxic? And the original drug is cheaper but harder to take? So… we’re just… doing the bare minimum? And calling it progress? 😐

India has been using primaquine for decades. You think your fancy western drugs are better? We know what works. You just don’t like the side effects. Stop complaining and take your pills like a man

There’s a deeper truth here: medicine isn’t just about science-it’s about access, dignity, and justice. A drug that saves lives but only for those who can pay or live near a lab… that’s not progress. That’s inequality with a prescription pad. We need global equity, not just better pills.