The world produces enough medicine to save billions. Yet 2 billion people still can’t get the drugs they need. Why? Because international trade rules, not supply or science, are standing in the way.

What TRIPS Actually Does

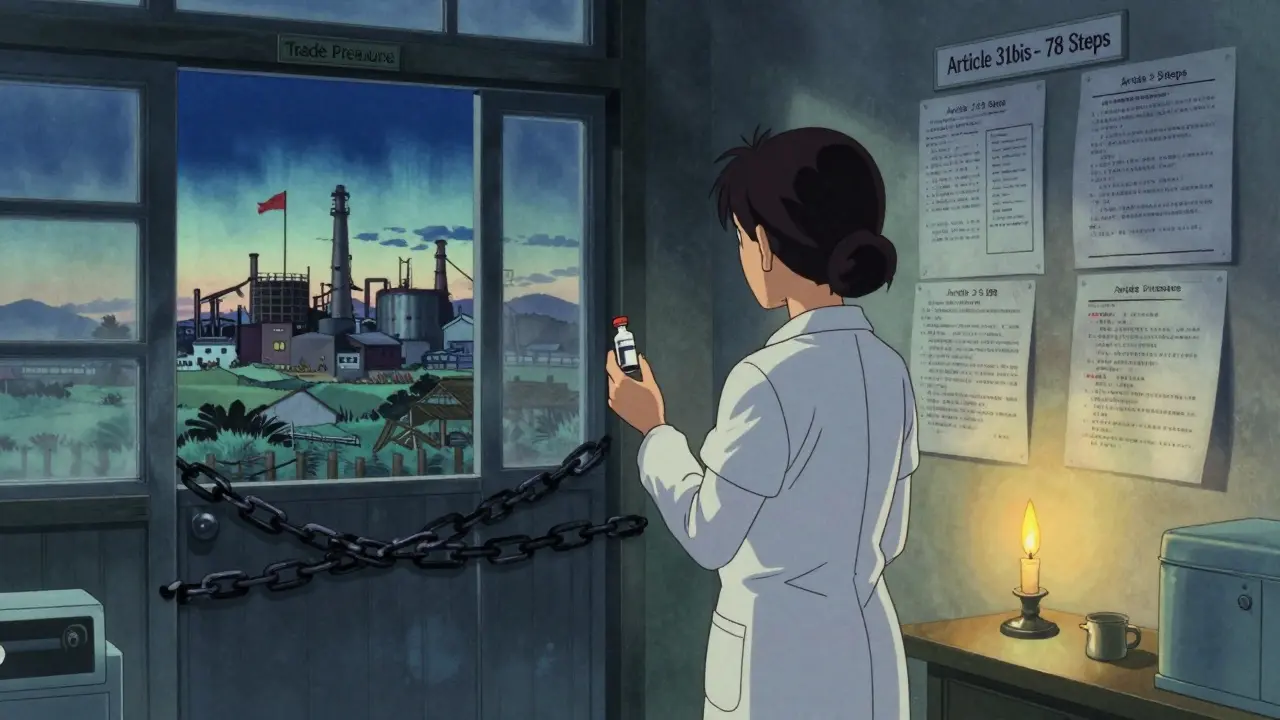

The TRIPS Agreement - short for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights - is a global rulebook written in 1994 and enforced since 1995. It’s part of the World Trade Organization (WTO) system. Its job? Make sure every country protects pharmaceutical patents the same way: 20 years from filing date, no exceptions. Before TRIPS, countries like India, Brazil, and Thailand could make their own generic versions of drugs. They didn’t have to wait for a company to patent a medicine. They could copy it, test it, and sell it for a fraction of the price. In India, a month’s supply of HIV drugs cost $10. After TRIPS, that same drug jumped to $10,000 if it was patented. TRIPS didn’t just affect HIV meds. It changed everything: cancer drugs, heart medications, antibiotics. Suddenly, every country had to lock away affordable versions of medicines behind legal barriers. The goal was to reward innovation. The result? A global access crisis.The Flexibility That Doesn’t Work

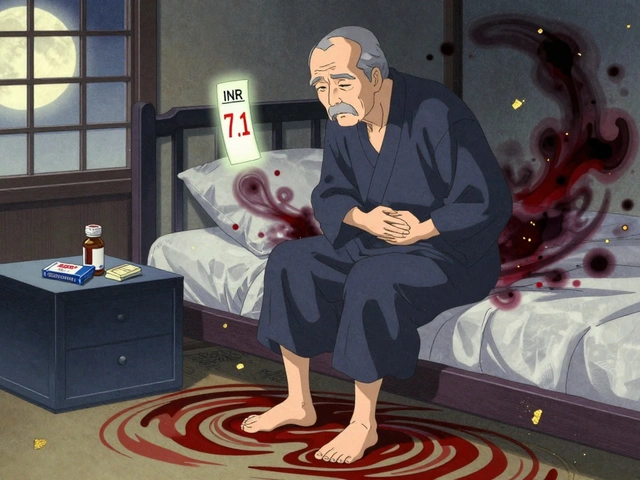

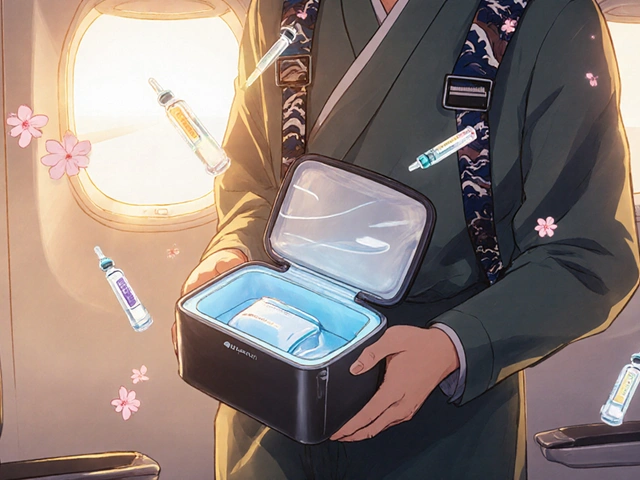

TRIPS isn’t completely rigid. It has escape hatches - called flexibilities. The biggest one is compulsory licensing. This lets a government say: “We need this drug now. We’re going to let a local company make it, even if the patent holder says no.” The government pays a fee. The patent holder still gets something. The public gets the medicine. In theory, this works. In practice? It’s broken. Article 31f of TRIPS says compulsory licenses can only be used to supply the country that issues them. That’s fine if you’re Brazil or India - you have factories. But what if you’re Rwanda, Malawi, or Nepal? You don’t make drugs. You need to import them. TRIPS blocked that. Until 2005. That year, the WTO added a tiny amendment: Article 31bis. It was supposed to fix the problem. Now, a country without manufacturing could import generics made under license in another country. Sounds simple, right? It’s not. The process requires 78 separate steps. Both the exporting and importing countries must file detailed notices with the WTO. The patent holder must be paid “adequate remuneration.” The medicine must be labeled for export only. The importing country must prove it has no domestic production capacity. All of this takes years. The only time it’s ever worked? Rwanda, 2012. They imported HIV drugs from Canada. It took four years. Médecins Sans Frontières helped them navigate the paperwork. The final price? Still 30% higher than if Rwanda had been able to make the drugs itself. Since then? Zero other successful uses.Why No One Uses the Rules

You’d think countries would use these flexibilities. After all, they’re legal. They’re written into the treaty. But they don’t. A 2017 study of 105 low- and middle-income countries found that 83% had never issued a single compulsory license. Why? Because of pressure. When Thailand issued licenses for HIV and cancer drugs in 2006, the U.S. removed its trade benefits. Thailand lost $57 million a year in exports. Brazil got placed on a U.S. “Priority Watch List.” South Africa faced a lawsuit from 39 drug companies in 2001 - until global protests forced them to back down. The threat isn’t just economic. It’s political. Pharmaceutical companies lobby. Diplomats call. Trade deals are held hostage. One country that tried to use a compulsory license for hepatitis C drugs told researchers they were warned: “Your next trade agreement will be harder.” Even when countries try, they’re outgunned. A 2019 Duke University study found that 92% of low-income countries had fewer than two full-time staff members handling intellectual property and medicines policy. Meanwhile, Big Pharma has teams of lawyers, lobbyists, and consultants working around the clock.

Voluntary Licensing: A Band-Aid on a Broken System

Pharmaceutical companies say they’re helping. They point to the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP), a voluntary program where companies license their patents to generic makers. Since 2010, MPP has helped bring down prices for HIV drugs in over 100 countries. But here’s the catch: MPP only covers 44 drugs - out of thousands. It doesn’t cover cancer, diabetes, or mental health drugs. It only works if the patent holder agrees. And they often don’t. In 2022, MPP covered just 1.2% of all patented medicines globally. And 73% of those licenses were only for sub-Saharan Africa - even though diseases like hepatitis C or tuberculosis are just as deadly in Southeast Asia or Latin America. Voluntary licensing is charity, not a right. And charity can be withdrawn.TRIPS-Plus: The Hidden Rules That Make Things Worse

Even if a country follows TRIPS, it’s not enough. Most countries now sign “free trade agreements” with the U.S., EU, or Japan - and those include TRIPS-plus clauses. These add extra restrictions:- Extending patent terms beyond 20 years

- Blocking generic approval until the patent expires (even if the patent is invalid)

- Requiring data exclusivity - meaning generic makers can’t even use the original company’s clinical trial data to prove their drug works

What Changed During the Pandemic?

In 2020, India and South Africa asked the WTO to waive TRIPS protections for COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. Their argument? A global emergency needs global access. After two years of delays, the WTO agreed - but only partially. The waiver covers only vaccines. Not diagnostics. Not treatments. Not future pandemics. And even that waiver has limits. It doesn’t force anyone to share technology. It doesn’t require patent holders to license their formulas. It doesn’t help countries that can’t produce vaccines even if they have the rights. The UN’s 2024 High-Level Meeting on Pandemics called for “reform of the TRIPS Agreement.” But reform hasn’t started. The same rules still apply.

The Real Cost of Patent Monopolies

The global pharmaceutical market is worth $1.42 trillion. But only 12% of prescriptions are for patented drugs. The rest? Generics. In the U.S., generics make up 89% of prescriptions. In low-income countries? Only 28%. Why? Because the drugs are priced out of reach. A single vial of insulin - a 100-year-old drug - costs $10 in India. $275 in the U.S. $1,200 in some parts of Latin America. The same cancer drug, imatinib, costs $30,000 a year under patent. In India, it’s $200. That’s a 99% drop. These aren’t hypothetical savings. They’re lives. When Thailand cut the price of HIV drugs by 80%, treatment coverage jumped from 20% to 80% in two years. When South Africa started using generics, the number of people on HIV treatment rose from 10,000 to over 4 million. The math is simple: no access to generics = more deaths.Where Do We Go From Here?

The system isn’t broken because it’s poorly designed. It’s broken because it was designed this way - to protect profits over people. The flexibilities exist. But they’re buried under bureaucracy, fear, and political threats. The answer isn’t more paperwork. It’s not more voluntary deals. It’s not waiting for a company to decide to be “nice.” It’s reform. Countries need to stop signing TRIPS-plus deals. They need to build legal teams to use compulsory licensing. They need to support regional manufacturing hubs - like Africa’s new vaccine production network in South Africa. The WTO needs to fix Article 31bis. Make it simple. Fast. Automatic. No 78-step forms. No political pressure. And if the system won’t change? Then it’s time to walk away from it. The right to health isn’t a privilege. It’s a human right. And no trade agreement should override that.What You Can Do

You might think this is a problem for governments and pharmaceutical companies. But it’s not. If you live in a wealthy country, you’re paying for this system. Your tax dollars fund drug research. Your insurance pays inflated prices. Your government pressures poorer nations to stay silent. Ask your representatives: Why are we blocking access to medicines? Why do we protect patents more than people? Support organizations pushing for reform: Médecins Sans Frontières, Knowledge Ecology International, the Access to Medicine Foundation. Demand transparency. Demand equity. Demand that the next global health emergency doesn’t cost another million lives because of a 30-year-old trade deal. The drugs exist. The technology exists. The money exists. What’s missing? The will.What is the TRIPS Agreement and why does it matter for generic medicines?

The TRIPS Agreement is a global treaty under the WTO that requires all member countries to grant 20-year patents on pharmaceutical products. This means drug companies can block others from making cheaper generic versions, even if the medicine is essential for public health. Before TRIPS, countries like India made low-cost generics for HIV and other diseases. After TRIPS, those prices skyrocketed - often by 100 times - making life-saving drugs unaffordable for millions.

Can countries still make generic medicines under TRIPS?

Yes - but it’s extremely difficult. TRIPS allows compulsory licensing, which lets governments authorize generic production without the patent holder’s consent. However, strict rules limit this: the medicine can only be made for domestic use unless a country has manufacturing capacity. Even then, importing generics from another country requires a complex, years-long process under Article 31bis - which has only been used successfully once, in 2012 by Rwanda.

Why haven’t more countries used compulsory licensing?

Most countries avoid it because of political and economic pressure. When Thailand issued licenses for HIV and cancer drugs in 2006, the U.S. removed its trade benefits, costing Thailand $57 million a year. Brazil and South Africa faced lawsuits and trade threats. Many low-income countries simply don’t have the legal staff or political courage to challenge powerful pharmaceutical companies and Western governments.

What’s the difference between compulsory licensing and voluntary licensing?

Compulsory licensing is a legal right under international law - a government can force a patent holder to allow generic production. Voluntary licensing is a business decision - a drug company chooses to let others make the drug. Voluntary deals, like those through the Medicines Patent Pool, have helped with HIV drugs but cover only 44 out of thousands of patented medicines. They’re not reliable, not comprehensive, and can be revoked at any time.

Are TRIPS-plus trade deals making things worse?

Yes. Many countries sign bilateral trade deals with the U.S. or EU that add extra patent protections beyond TRIPS - like extending patent terms by 4-5 years or blocking generic approval even after a patent expires. These “TRIPS-plus” rules have been added in 86% of WTO member countries, reducing the chances of affordable medicines reaching patients by an estimated $2.3 billion annually across 34 low- and middle-income countries.

Did the COVID-19 vaccine waiver fix the problem?

No. The 2022 WTO waiver only applies to vaccines - not treatments, diagnostics, or future pandemics. It doesn’t require technology transfer, doesn’t force companies to share formulas, and doesn’t help countries without manufacturing capacity. It’s a symbolic gesture that didn’t change the core problem: patents still block access to essential medicines.

Okay, let’s be real: TRIPS isn’t a trade agreement-it’s a corporate handshake disguised as law. 20-year patents? On life-saving drugs? That’s not innovation-it’s extortion. And don’t get me started on Article 31bis-78 steps? Who designed this, a bureaucrat with a caffeine addiction? Rwanda’s one success story? That’s not a fix-it’s a miracle. And yet, we act like this is normal? No. It’s a moral failure dressed in legalese.

i just read this and cried a little… like, how is this still a thing? we have the tech, the money, the science… but people are dying because of paperwork and lawyers? that’s not capitalism, that’s just cruel. pls someone fix this. 🥺

you think this is about patents? nah. this is the deep state. the pharmaceutical industry is a front for the global elite to control populations. they don’t want you healthy-they want you dependent. why do you think they blocked the vaccine waiver for treatments? because if you could cure hepatitis C or diabetes for $5, the whole system collapses. they’d rather kill 2 billion than lose a profit margin. read the fine print. it’s all connected.

people don’t understand innovation requires incentive. if you take away patents you kill the future. no one will spend 10 years and 2 billion dollars研发 a drug if some country in Africa can just copy it. this isn’t about greed-it’s about survival of the system. you want cheap drugs? fine. but then you get no new cancer drugs next decade. tradeoffs exist. stop acting like morality is a magic wand.

ugh i hate how this gets framed like it’s a debate. it’s not. it’s a human rights issue. if your kid needs insulin and you can’t afford it, it doesn’t matter if the patent is ‘legal.’ it’s still wrong. and honestly? the U.S. government is part of the problem. we pressure other countries not to use the flexibilities. we’re not the good guys here. time to grow up.

just wanted to say… i’ve worked in public health for 15 years. i’ve seen this play out in 8 countries. the moment a country tries to use compulsory licensing? the phone calls start. the ‘trade review’ letters arrive. the diplomats show up with ‘friendly advice.’ it’s not about law. it’s about power. and the little guys always lose. the system isn’t broken. it’s working exactly as designed.

wait so if a country cant make drugs can they even import them? like what if they have no factories? the 78 step thing sounds like a joke… also why is canada the only one who exported? did they just get lucky? 🤔

the fact that this is even a conversation is insane. 💀 we’re talking about people dying because of corporate lawyers. and we’re still arguing about ‘incentives’? bro. we had a pandemic. we had 7 million dead. and the answer was… a waiver for vaccines only? and it still didn’t force tech sharing? this isn’t capitalism. this is a horror movie. and we’re all just watching. 🤡 #TRIPSisMurder