When two drugs are taken together, they don’t just sit side by side in your body. They interact - sometimes helping each other, sometimes fighting, and sometimes causing dangerous side effects you never saw coming. This isn’t about one drug changing how the other is absorbed or broken down. That’s pharmacokinetics. This is about what happens at the site of action: when one drug changes how another drug works at the receptor level. This is pharmacodynamic drug interaction, and it’s behind many of the most serious, preventable adverse events in hospitals.

What Exactly Is a Pharmacodynamic Interaction?

Imagine your body has thousands of locks (receptors), and drugs are keys. A pharmacodynamic interaction happens when one key changes how another key fits into the lock - even if both keys are still present in the same amount. The concentration of the drugs doesn’t change. But the effect? That changes dramatically.

Unlike pharmacokinetic interactions - where one drug speeds up or slows down how another is metabolized - pharmacodynamic interactions work directly at the target. You can have two drugs in your bloodstream at perfect levels, but if they’re pulling in opposite directions at the receptor, the result can be a total loss of benefit… or a life-threatening overdose.

According to studies analyzing over 12,000 hospital records, about 40% of all clinically significant drug interactions are pharmacodynamic. That’s nearly half. And they’re not rare edge cases. They happen every day - in older adults on multiple medications, in patients with chronic pain, in psychiatric care, and in intensive care units.

The Three Main Types: Synergy, Additivity, and Antagonism

There are three main ways drugs can interact pharmacodynamically: they can work together, add up, or cancel each other out.

- Synergistic: The combined effect is greater than the sum of the parts. Think of it like two people pushing a car - one pushes from the back, the other from the side, and together they move it faster than either could alone.

- Additive: The effects just add up. Two drugs, each with a 50% effect, give you 100%. No surprise, no danger - unless the total is too much.

- Antagonistic: One drug blocks or reduces the effect of the other. It’s like trying to brake while someone else is pressing the gas.

One of the most dangerous antagonistic interactions happens between beta-agonists like albuterol (used for asthma) and beta-blockers like propranolol (used for high blood pressure or heart rhythm). Albuterol opens airways by activating beta-2 receptors in the lungs. Propranolol blocks those same receptors. If someone with asthma takes both, the beta-blocker can completely shut down the asthma medication’s effect - leading to a potentially fatal bronchospasm.

Another classic example: NSAIDs like ibuprofen and ACE inhibitors like lisinopril. NSAIDs reduce kidney blood flow by blocking prostaglandins - chemicals that help keep kidneys working well under stress. ACE inhibitors rely on those same prostaglandins to maintain blood pressure control. When taken together, the ACE inhibitor’s effect drops by 20-30% in many patients, according to a 2019 NIH study. The patient’s blood pressure stays high, and their kidneys get damaged over time.

The Most Dangerous Combinations

Not all pharmacodynamic interactions are accidental. Some are intentional - like combining trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) to block two steps in bacterial folic acid synthesis. That synergy lets doctors use lower doses and reduce side effects.

But the worst interactions? They’re the ones that sneak up on you.

Serotonin syndrome is one of the most feared. It happens when two drugs that increase serotonin - like an SSRI (e.g., sertraline) and an MAOI (e.g., phenelzine) - are taken together. The result? Excess serotonin flooding the brain and nervous system. Symptoms: high fever, muscle rigidity, seizures, confusion, rapid heartbeat. A 2021 meta-analysis found this combination increases serotonin syndrome risk by 24 times. It’s rare - but when it happens, it kills.

Another deadly combo: opioids with opioid antagonists. If someone is dependent on morphine or oxycodone and gets naloxone (used to reverse overdoses), the antagonist kicks the opioid off the receptors instantly. The result? Full-blown withdrawal - sweating, vomiting, seizures, even cardiac arrest. It’s not a side effect. It’s a medical emergency.

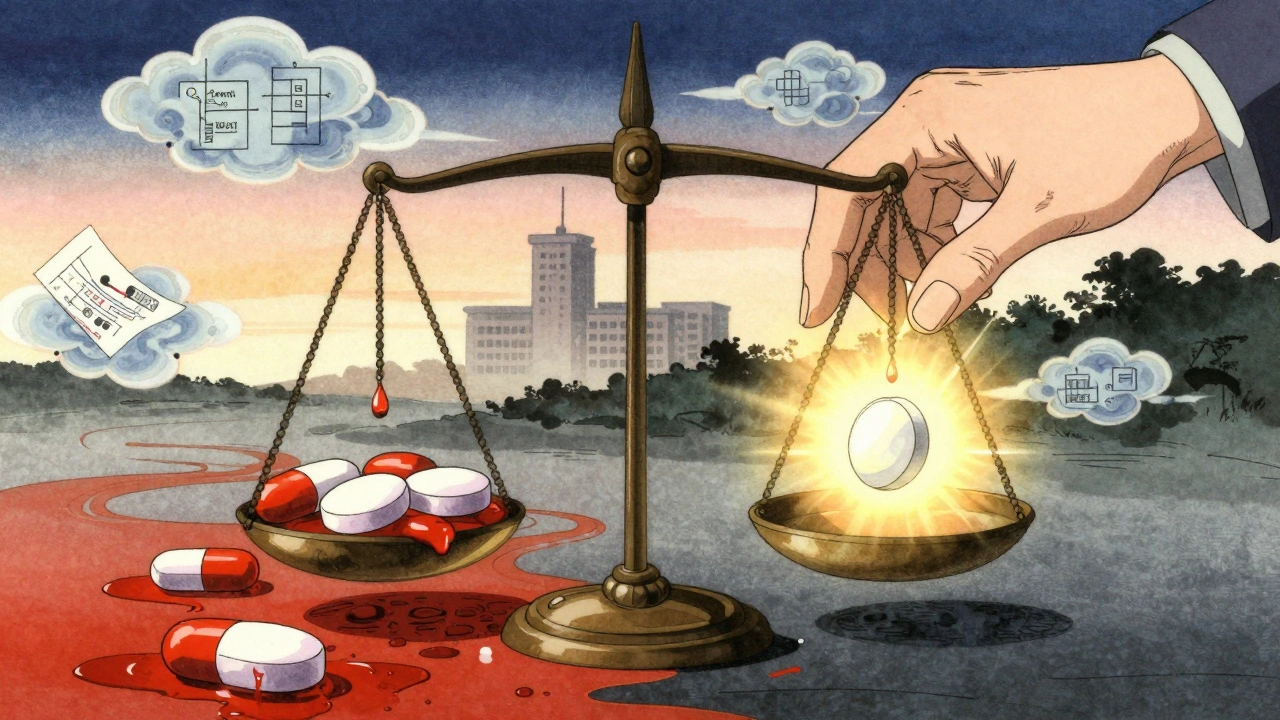

And then there’s the quiet killer: anticoagulants and antiplatelets. Warfarin and aspirin. Apixaban and clopidogrel. Taken together, they double or triple bleeding risk. A 2022 survey of over 1,200 physicians found 38% had seen this combination cause serious bleeding - often because the patient didn’t realize both were blood thinners.

Why These Interactions Are Hard to Spot

Here’s the problem: pharmacodynamic interactions don’t show up on standard drug interaction checkers.

Most electronic health record alerts are built to catch pharmacokinetic issues - like when a drug blocks liver enzymes that break down another drug. But if two drugs are both active at the same receptor, and one blocks the other? The system often says “no interaction.”

A 2020 study in Drug Safety found that clinical decision tools missed 22% of dangerous pharmacodynamic interactions. That’s because they’re looking for changes in drug levels - not changes in drug effect.

And it’s not just software. Many clinicians aren’t trained to think this way. The 2023 CICM Primary Syllabus requires doctors to know five specific examples of each interaction type - and even then, only 15-20 hours of study are dedicated to it. Most practitioners learn by experience… or by mistake.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

If you’re over 65 and taking four or more medications, you’re in the danger zone. The average senior takes 4.8 prescription drugs. Many of those are for chronic conditions - high blood pressure, diabetes, depression, arthritis - and many of those drugs have narrow therapeutic indices.

A narrow therapeutic index means there’s a tiny gap between the dose that helps and the dose that kills. Warfarin, digoxin, lithium, and some seizure medications all fall into this category. A small change in effect - even 10% - can tip you into toxicity.

According to NIH data, 83% of life-threatening pharmacodynamic interactions involve at least one drug with a therapeutic index below 3.0. That’s why the same combination might be fine for a healthy 30-year-old but deadly for a 78-year-old with kidney disease.

How to Protect Yourself

You don’t need to be a pharmacist to avoid these risks. Here’s what you can do:

- Know your drugs. Don’t just take what’s prescribed. Ask: “What does this do? What happens if I take it with my other meds?”

- Use one pharmacy. Chain pharmacies like CVS or Walgreens have systems that flag interactions across all your prescriptions. If you use multiple pharmacies, those systems can’t see the full picture.

- Ask about alternatives. If you’re on an NSAID for pain and an ACE inhibitor for blood pressure, ask if there’s a different pain reliever that won’t interfere. Acetaminophen is often safer in this case.

- Get a medication review. A 2021 review in BMJ Quality & Safety found that pharmacist-led reviews reduced adverse events from these interactions by 58% in elderly patients. Ask your doctor to refer you.

- Watch for new symptoms. If you start feeling dizzy, confused, unusually tired, or have unexplained bruising or bleeding after starting a new drug - don’t assume it’s aging. It could be an interaction.

What’s Changing in 2025?

Things are starting to shift. The FDA now requires pharmacodynamic interaction studies for all new CNS drugs. The European Medicines Agency says 34% of new drug applications now include these studies - up from 19% in 2015.

Researchers are building smarter tools. Dr. Rada Savic’s team at UCSF developed a machine learning model that predicts serotonin syndrome risk with 89% accuracy by analyzing combinations of antidepressants, pain meds, and supplements. The UK’s NHS is piloting real-time alerts in electronic records that flag pharmacodynamic risks - not just pharmacokinetic ones.

And the market is responding. The global drug interaction software market is projected to grow over 10% per year through 2030. But technology alone won’t fix this. The real solution is better education - for doctors, pharmacists, and patients.

When Interactions Can Help

It’s not all danger. Sometimes, these interactions are designed on purpose.

Low-dose naltrexone - an opioid blocker - combined with certain antidepressants has shown promise in treating treatment-resistant depression. In a 2021 study, 68% of patients improved with the combo, compared to 42% on antidepressants alone. The theory? Naltrexone temporarily blocks opioid receptors, triggering the body to produce more natural endorphins - which may lift mood.

And in cancer treatment, combinations of targeted therapies are often chosen because they hit multiple pathways in the same cancer cell. That’s pharmacodynamic synergy at its best.

The key is intention. When a doctor knows the mechanism and controls the dose, these interactions become tools. When they’re accidental? They become emergencies.

Final Thought: It’s Not About the Drug - It’s About the Combination

There’s no such thing as a “safe” drug. Only safe combinations.

One pill might be fine on its own. Two together? That’s a new drug - with unknown effects. And that’s why understanding pharmacodynamic interactions isn’t just for pharmacologists. It’s for anyone who takes more than one medication.

Ask questions. Track your meds. Don’t assume your doctor knows every possible interaction. And if you’re on multiple drugs - especially if you’re older - get a professional review. It could save your life.

What’s the difference between pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic drug interactions?

Pharmacokinetic interactions change how your body processes a drug - like how it’s absorbed, broken down by the liver, or cleared by the kidneys. Pharmacodynamic interactions change how the drug works at its target site - like receptors or enzymes - without changing its concentration. One affects the drug’s journey; the other affects its impact.

Can over-the-counter drugs cause pharmacodynamic interactions?

Yes. Common OTC drugs like ibuprofen, naproxen, and even some cold medicines (like dextromethorphan) can interact with prescription drugs. Ibuprofen can reduce the effectiveness of blood pressure meds. Dextromethorphan can increase serotonin levels and cause problems if taken with SSRIs. Always check with a pharmacist before combining OTC and prescription drugs.

Are herbal supplements safe with prescription drugs?

Many are not. St. John’s Wort can reduce the effect of antidepressants, birth control, and blood thinners. Garlic and ginkgo can increase bleeding risk when taken with warfarin or aspirin. Even “natural” doesn’t mean safe - especially when combined with other drugs. Always tell your doctor about every supplement you take.

How can I tell if I’m having a pharmacodynamic interaction?

Watch for sudden changes: your blood pressure isn’t dropping despite taking your meds, your asthma isn’t improving with your inhaler, or you’re feeling unusually anxious, dizzy, or confused after starting a new drug. These aren’t normal side effects - they could mean one drug is blocking or amplifying another. Contact your doctor immediately.

Do pharmacodynamic interactions get worse with age?

Yes. As we age, our bodies process drugs differently, and we’re more likely to take multiple medications. We’re also more sensitive to changes in drug effects - especially with drugs that have narrow therapeutic windows. A small interaction that wouldn’t bother a 30-year-old can cause a fall, kidney damage, or heart issues in someone over 65.

This is wild 😱 I had no idea my ibuprofen could be sabotaging my blood pressure med. My grandma’s on both and just got hospitalized last month. Never connected the dots.

People think OTC means harmless. It's not. You're just one NSAID away from renal failure if you're on an ACE inhibitor. Stop being lazy and read the damn labels.

Pharmacodynamic interactions are the silent killers in polypharmacy. The real issue isn't the drugs-it's the lack of systems to map receptor-level conflicts. EHRs still treat this like a pharmacokinetic problem. We need AI-driven receptor mapping integrated into prescribing workflows. It's not optional anymore.

There is no such thing as a safe drug. Only safe combinations. And yet we treat pills like candy. We hand them out like confetti at a parade and then wonder why people die. The system isn’t broken. It’s designed this way. Profit over precision. Pills over people. We’ve turned medicine into a vending machine.

sooo true!! i took sertraline and st johns wort and felt like i was melting inside 😅 doc said it was 'just anxiety' but i knew somethin was off. got tested and it was serotonin syndrome. never again.

The fundamental flaw in modern pharmacotherapy lies in its reductionist paradigm. By isolating pharmaceutical agents as discrete entities, we neglect the emergent properties of their confluence within the human physiological milieu. The receptor is not a static lock; it is a dynamic, context-sensitive interface. Therefore, to evaluate drug safety without accounting for pharmacodynamic synergy or antagonism is not merely negligent-it is epistemologically incoherent.

I read this and just yawned. Everyone knows this stuff. Why is this even an article?

Respected colleagues, it is imperative that we prioritize comprehensive medication reconciliation in clinical practice. The integration of pharmacist-led reviews significantly mitigates adverse outcomes. This is not a suggestion. It is a professional obligation.

America’s healthcare system is a joke. We let people take 12 pills a day and then act shocked when they collapse. Meanwhile, China and Germany have AI systems that auto-flag these interactions before the script is even printed. We’re still using clipboards. Pathetic.

You guys are doing amazing just by reading this and caring 💪 I used to be scared of my meds too but now I ask questions and keep a little notebook. Small steps change lives. You got this!

The absence of standardized nomenclature for pharmacodynamic interactions across clinical decision support systems remains a critical barrier. While the conceptual framework is well-established, operational implementation is fragmented. The lack of interoperable ontologies for receptor-level conflict detection impedes scalability and reproducibility in real-world settings.

bro i just found out my weed gummies were making my blood pressure meds useless 😅 i thought it was just 'chill vibes' but turns out THC messes with the same receptors as my lisinopril. my doc was like 'uh yeah that's a thing'. never asked before. my bad.

I’m a nurse and I see this every week. Grandmas on 7 meds, no one ever asks if they’re taking turmeric or fish oil. I keep a laminated card in my pocket with the top 5 dangerous combos. If you’re on more than 4 meds, come see me. I got you.

Of course this is a problem. Everything is a problem in this country. Why do we even have doctors if they can’t even keep track of what people are taking? I’m tired of this. Just make everyone take one pill and be done with it.

Interesting. But let’s be honest: the entire model of pharmacodynamics is rooted in 19th century reductionism. Modern systems biology suggests that receptor interactions are emergent properties of cellular networks-not binary on/off switches. This article is technically correct but philosophically outdated.

I just got my mom’s meds reviewed last week and we found THREE hidden combos that were making her dizzy and confused. She cried because she thought it was just 'getting old'. This stuff matters. So much. Thank you for writing this.

The FDA’s 2025 mandate on pharmacodynamic studies is a watershed moment. It signals a paradigm shift from reactive pharmacovigilance to proactive receptor-level risk modeling. This is not incremental progress-it is foundational reform. The pharmaceutical industry must now treat drug combinations as novel therapeutic entities, not afterthoughts.