When you hear about a new cancer drug in the news, it’s easy to assume it’s available to anyone with that type of cancer. But the truth is, most experimental treatments don’t work for everyone-even if they’re designed for your specific cancer. That’s where clinical trial eligibility comes in. It’s not just about age or stage of disease anymore. Today, your tumor’s biology, your genes, and even your blood markers decide whether you qualify for a trial. This shift isn’t just technical-it’s personal. It means some patients get access to life-changing therapies while others don’t, not because of luck, but because of measurable biological signals called biomarkers.

What Are Biomarkers, Really?

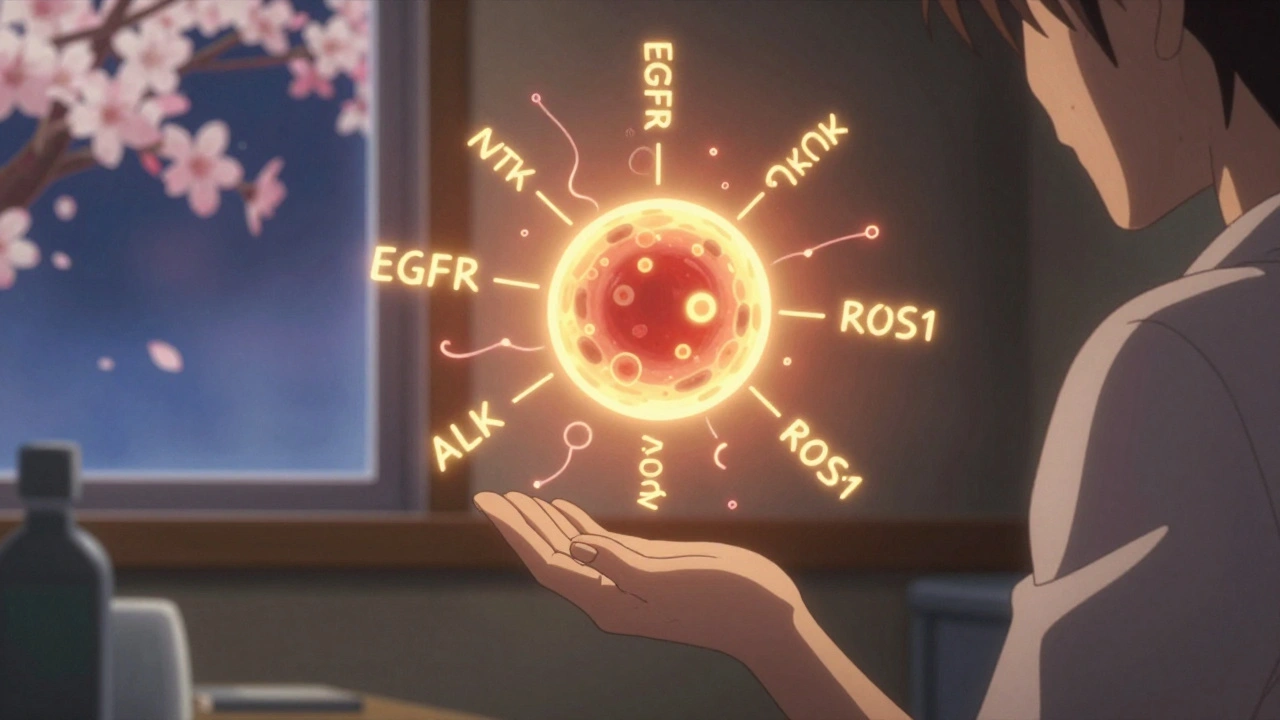

Biomarkers aren’t fancy lab jargon. They’re measurable signs in your body that tell doctors something important. Think of them like a car’s check engine light, but for your cancer. They can be genes, proteins, or even molecules in your blood or tissue that show whether a tumor is likely to respond to a certain drug. The FDA recognizes seven types of biomarkers, but for cancer trials, three matter most:- Predictive biomarkers tell you if a drug will work for you. For example, if your lung cancer has an EGFR mutation, you might respond to osimertinib. Without that mutation, the drug likely won’t help.

- Prognostic biomarkers show how aggressive your cancer is, regardless of treatment. A high level of PSA in prostate cancer, for instance, often means faster progression.

- Pharmacodynamic biomarkers show whether the drug is doing what it’s supposed to do in your body-like lowering a specific protein after treatment.

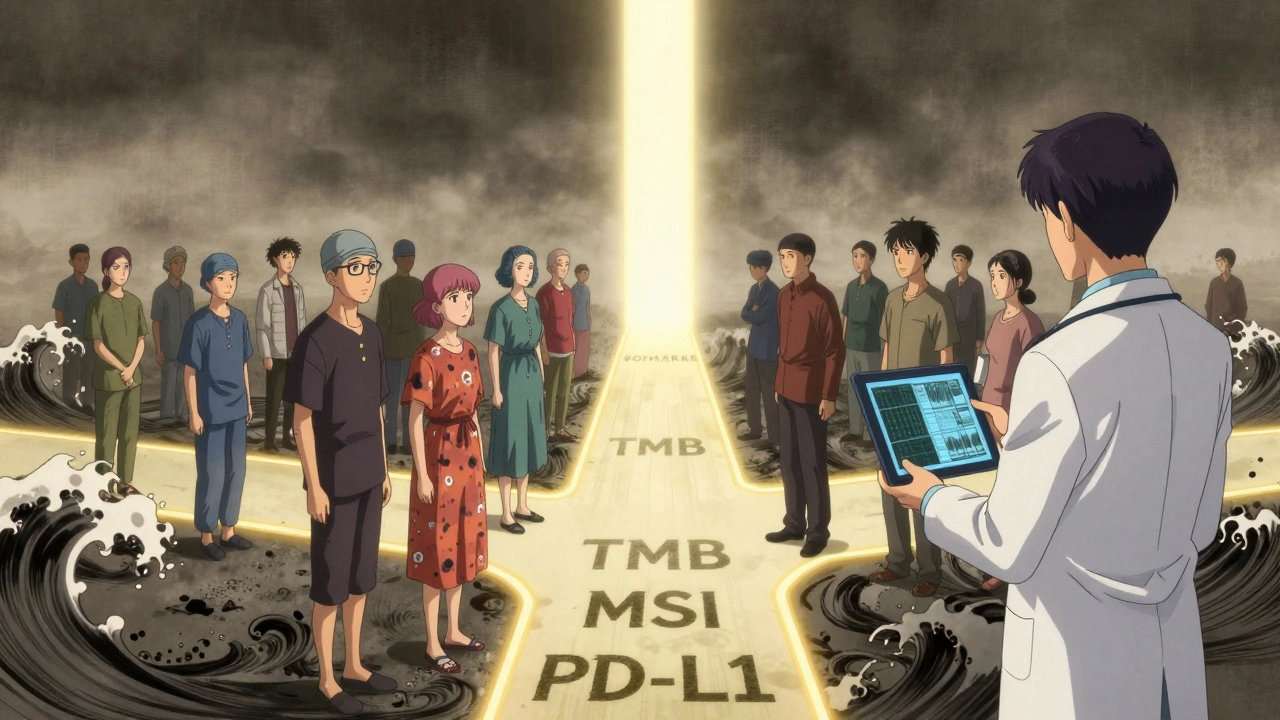

In 2022, 92% of new cancer drug approvals by the FDA came with a biomarker requirement. That means if you don’t have the right marker, you’re automatically excluded from the trial-even if you’re otherwise healthy and eligible. This isn’t discrimination. It’s precision. Trials that use biomarkers have nearly double the chance of success compared to those that don’t.

Why Inclusion Criteria Are More Than Just Rules

Inclusion criteria are the checklist doctors use to decide who gets in. Traditionally, they were simple: age, cancer stage, previous treatments. Now, they’re layered. A typical cancer trial might require:- Stage III or IV non-small cell lung cancer

- At least one prior chemotherapy

- ECOG performance status of 0 or 1 (meaning you’re up and about most of the day)

- Confirmed ALK or ROS1 gene rearrangement via tissue biopsy

- No active brain metastases

- Normal kidney and liver function

That last one-gene rearrangement-is the game-changer. It’s not enough to have lung cancer. You need the *right kind* of lung cancer. That’s why screening failure rates used to be 70% in older trials. Now, with biomarker screening, they’ve dropped to 35% in some studies. But here’s the catch: you need that test done right.

Not all labs are created equal. If your biopsy sample was stored wrong, or if the test was done in a non-CLIA-certified lab, the results might be unreliable. That’s why most trials require testing through approved centers. If your local hospital can’t do the test, you might need to travel-or wait weeks for results. And in cancer, time isn’t just money. It’s survival.

The Hidden Costs of Biomarker Testing

Biomarker-driven trials sound perfect on paper. But behind the scenes, they’re messy. A 2023 survey of 142 cancer trial sites found that sites with established biomarker testing enrolled patients 28 days faster than those without. But getting to that point isn’t easy.Here’s what goes into making it work:

- Training: Staff need 120-160 hours of extra training compared to traditional trials. That’s not just reading a manual-it’s learning how to handle tissue samples, interpret reports, and explain results to patients.

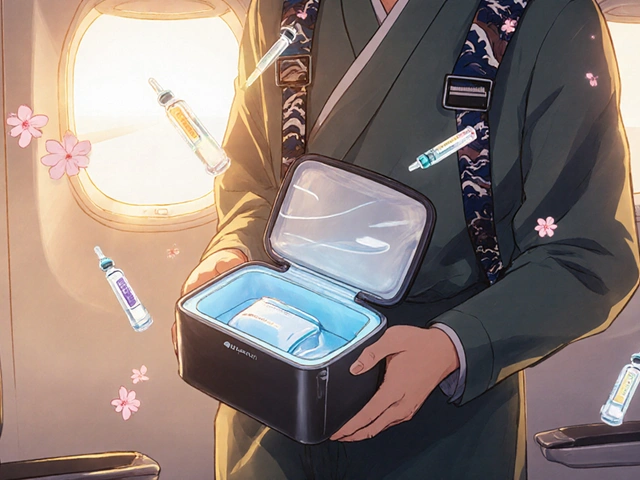

- Logistics: Tissue samples often need to be shipped to central labs. If the sample degrades during transit, the test fails. That means special coolers, overnight shipping, and strict timelines.

- Timing: Biomarker results can take 7-14 days. For someone with aggressive cancer, that’s a lifetime. Some trials now use liquid biopsies-blood tests that detect tumor DNA-to cut that time to 3-5 days.

- Consistency: If one site uses one test and another uses a different one, results can vary. That’s why 82% of sponsors report inconsistent testing across sites. Standardized kits and centralized labs are becoming the norm.

And then there’s geography. A biomarker like HLA-A*02:01 is common in Europe (up to 54% of people) but rare in parts of Asia (as low as 17%). A trial designed in the U.S. might fail in India-not because the drug doesn’t work, but because too few patients have the right marker. Global trials now have to plan for these differences upfront.

What Happens When You Don’t Qualify?

It’s heartbreaking when you’re told you don’t qualify. You’ve done your research. You’ve traveled. You’ve hoped. And now you’re told, “Your tumor doesn’t have the marker.”But here’s the thing: not qualifying doesn’t mean you’re out of options. Many trials now offer “basket” or “umbrella” designs. That means you might be enrolled in a different arm of the same study based on your actual biomarker profile. For example:

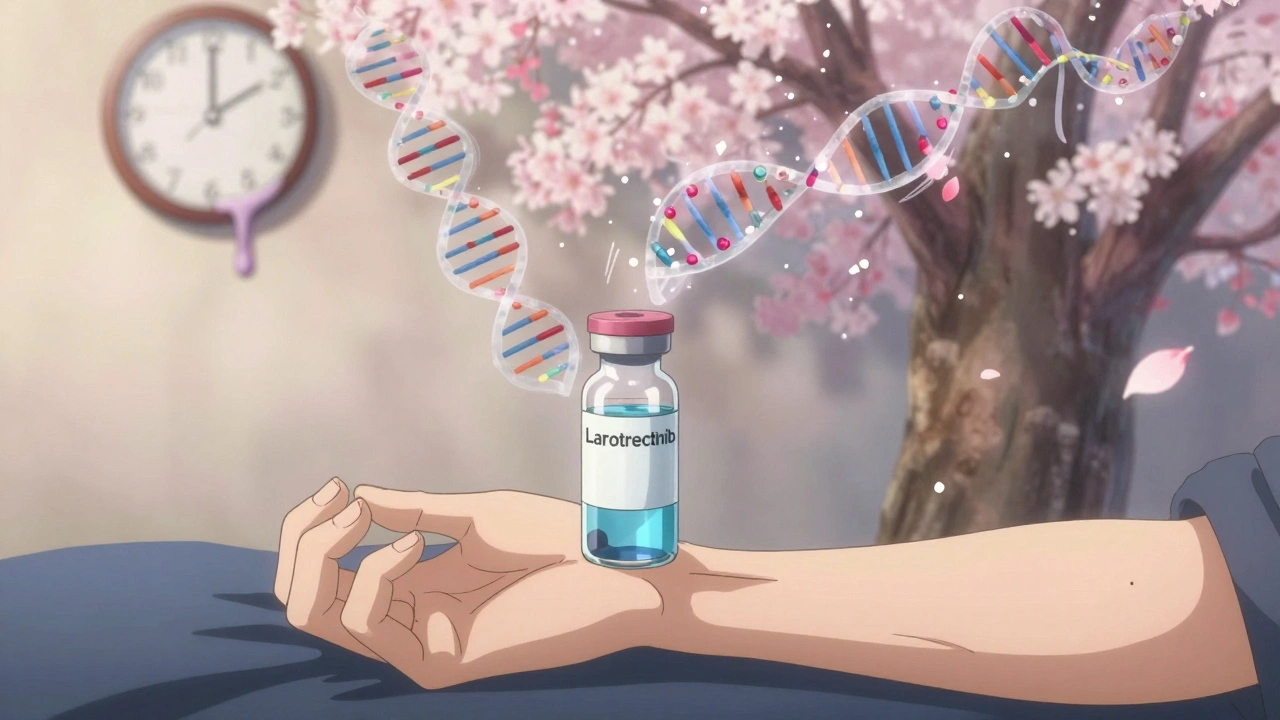

- If you have an NTRK fusion, you might get larotrectinib-even if your cancer is in your colon, not your lung.

- If you have a high tumor mutational burden (TMB), you might qualify for immunotherapy even if your cancer isn’t traditionally responsive.

Some patients are even retested later. Tumors change over time. A biopsy from six months ago might not reflect what’s happening now. A repeat biopsy or liquid biopsy could open new doors.

And if no trial fits? Your oncologist might still use the drug off-label if there’s strong evidence. Or you might qualify for expanded access programs. Don’t give up after one “no.” Ask: “Is there another test we can do? Is there another trial?”

The Future Is Multi-Omic and Real-Time

The next wave of clinical trials isn’t just about one gene. It’s about the whole picture. That’s called multi-omic testing-looking at genes, proteins, metabolites, and immune markers all at once. By 2025, 65% of new cancer trials are expected to use these panels.Some trials are already using AI to find hidden patterns in data. For example, an algorithm might notice that patients with a certain combination of three proteins respond better than those with just one. That’s not something a human would spot easily.

Real-world data is also becoming part of eligibility. Instead of waiting for years of trial data, researchers are now using electronic health records from thousands of patients to validate biomarkers faster. Companies are even testing decentralized collection-sending home kits for blood or saliva samples-so you don’t have to come in for every test.

And the regulatory agencies are catching up. The FDA’s biomarker qualification process, which used to take two years, now takes 18 months. Approval rates have jumped from 58% to 73%. That means more biomarkers will become standard faster.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you or someone you know is considering a cancer clinical trial:- Ask for biomarker testing. Don’t assume it’s automatic. Request a comprehensive genomic profile (CGP) or next-generation sequencing (NGS) test.

- Know your results. Get a copy of the report. Don’t just take the doctor’s word. Look for terms like “mutation,” “amplification,” “fusion,” or “expression level.”

- Check clinicaltrials.gov. Use filters for “biomarker” and your specific cancer type. You can even search by the exact gene or protein.

- Ask about central testing. If your hospital can’t do the test, ask if the trial has a central lab. They’ll often ship you a kit.

- Don’t accept “no” as final. Ask: “Could I be retested in six months?” or “Is there a trial for patients like me without this marker?”

Biomarker-based eligibility isn’t perfect. It’s expensive, complex, and unevenly available. But it’s also the most effective way we have to match the right drug to the right patient. It’s not about exclusion-it’s about inclusion for those who stand to benefit the most.

What used to be a one-size-fits-all approach is now a tailored fit. And for many, that’s the difference between hope and despair.

What is the most common biomarker used in cancer clinical trials?

The most common biomarkers vary by cancer type. In non-small cell lung cancer, EGFR, ALK, ROS1, and PD-L1 are routinely tested. In breast cancer, HER2 and hormone receptors (ER/PR) are standard. In melanoma, BRAF V600E mutations are critical. For many newer trials, tumor mutational burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI) are becoming key across multiple cancers.

Can I get a biomarker test done before I join a trial?

Yes, and it’s strongly encouraged. Many oncologists now order comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) as part of standard care, especially for advanced cancers. If your insurance covers it, you can get tested before even looking at trials. This saves time and helps you identify which trials you might qualify for. Some hospitals have dedicated molecular tumor boards that review your results and suggest options.

Why do some biomarker tests take so long?

Complex tests like next-generation sequencing require specialized equipment and expertise. Samples often need to be shipped to central labs, which can take days. Some tests require tissue from a biopsy, which may not be available or may be too small. Liquid biopsies (blood tests) are faster-often 3-5 days-but aren’t always as accurate for early-stage disease. Turnaround time is one of the biggest delays in trial enrollment.

What if my biomarker test comes back negative?

A negative result doesn’t mean you’re out of options. Some trials don’t require biomarkers at all. Others use different markers you haven’t been tested for yet. Also, tumors evolve. A test from six months ago may not reflect your current cancer biology. Ask about retesting, especially if your cancer has progressed. You might also qualify for trials testing drugs for patients without known markers.

Are biomarker-based trials only for advanced cancer?

No. While most biomarker trials focus on advanced or metastatic disease, there are growing numbers for early-stage cancers. For example, trials now use biomarkers to determine who needs chemotherapy after surgery, or who might benefit from immunotherapy before surgery. The goal is to avoid overtreating low-risk patients and focus powerful drugs on those who need them most.

What Comes Next?

The future of cancer care isn’t just about better drugs. It’s about smarter matching. Biomarkers are the key. But they’re only useful if they’re accessible, reliable, and understood. Right now, there’s a gap between what science can do and what most patients can access. That’s changing-but slowly.If you’re in the system, advocate for testing. If you’re a caregiver, ask questions. If you’re a doctor, push for standardization. The goal isn’t to make trials harder. It’s to make them more effective-for everyone who walks through the door.

Just had my third round of chemo and got the NGS report back 🤯 Turns out I’ve got that EGFR exon 19 del-so I’m in for the new TKI trial. Feels like winning the genetic lottery when you’re fighting for your life. Thanks for breaking this down so clearly.

So now you need a PhD just to get into a trial

I work in oncology nursing and I see this every day. The biomarker testing is life-changing-but the delays? Heartbreaking. One patient waited 18 days for her liquid biopsy results. By then, her tumor had spread. We’re using central labs now and it’s cut wait times in half. But not everywhere has the funding. If you’re reading this and you’re in a position to help-advocate for better lab access. It’s not just science, it’s survival.

Oh great so now we’re genetically sorting people like cattle. Next they’ll be charging extra for the 'premium mutation' package. America’s healthcare system is a glitchy video game where only the lucky players get the cheat codes. Meanwhile, my cousin in India can’t even get a basic CT scan. This isn’t precision medicine-it’s elitist science theater

It is imperative to underscore the profound transformation that biomarker-driven oncology has wrought upon the landscape of therapeutic intervention. The paradigm shift from empirical, population-based treatment modalities to individualized, molecularly stratified interventions represents not merely an advancement, but a quantum leap in clinical efficacy. One must acknowledge, however, that the logistical and infrastructural burdens imposed upon under-resourced institutions may inadvertently exacerbate disparities in access, thereby undermining the very equity that precision medicine purports to champion.

Everyone in the US talks about biomarkers like they’re magic. In India, we don’t even have basic pathology labs in half the villages. You think a poor guy in Bihar with lung cancer gets an NGS test? Please. This whole system is designed for rich Westerners. The real biomarker here is your bank account.

I’ve seen patients cry because they were told they didn’t have the right mutation. But I’ve also seen them come back months later with a new biopsy and a new hope. Tumors change. People change. And sometimes, the system catches up. Don’t let one negative result be the end of your story. Keep asking. Keep pushing. There’s always another door. I’ve had patients get into trials after two years of waiting. You’re not alone.

The entire clinical trial infrastructure is a bureaucratic farce. Biomarker testing is not a diagnostic tool-it’s a gatekeeping mechanism disguised as science. The FDA approves drugs based on 200-patient cohorts while ignoring real-world heterogeneity. This isn’t innovation. It’s regulatory theater masking systemic failure.

PD-L1 expression thresholds are still arbitrary. One lab says 1%, another says 50%. The same tumor, two different answers. And then they wonder why trials fail. Standardization isn’t optional-it’s the baseline. We need FDA-certified, real-time QC pipelines. No more guesswork. This is cancer, not a college lab project.

Biological destiny > American luck. 🌌

They say biomarkers are the future but what if they’re just a distraction? What if the real cure is in diet, sleep, and reducing stress? Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know that. They profit from tests, not healing. And don’t get me started on how they manipulate mutation data to push expensive drugs. It’s all a scam. Trust your gut, not the lab report.

Man, I’m from Mumbai and my cousin got into a trial in Toronto because her tumor had ROS1. Her local hospital said ‘no test available.’ She mailed her biopsy sample to Canada. They got it in 3 days. She’s in remission now. This system is broken-but people still find a way. That’s the real biomarker: stubborn hope.